Over the past few months, the Centre for Relational Care’s Humans of Care series has gathered stories from young people, parents, carers and workers within the out-of-home care system. These stories reveal the significance of relationships and how we need to put our humanity back in before our bureaucracy. These are the lived experiences that show us where the system works and where it fails. We acknowledge and thank the storytellers for trusting us with their stories. This piece exists because they were brave enough to say: this happened, and it mattered.

Here we have shared some of the insights from these important stories (all names below have been changed to protect privacy.)

Rigid policies over real relationships

When a policy is applied without regard for context or the actual person involved, it doesn't protect. It isolates. It tells young people and their families that bureaucratic procedure matters more than their lives.

Clare wasn't allowed to attend her Pop's funeral because he wasn't biologically related. He'd married her Nanny before she was born and raised her as his own. When the caseworker said they couldn't ensure her safety without that biological connection the “system” was saying that grief requires blood relations.

Amira was 12 when her sister got married by the beach. She'd been invited alongside her brothers and father. But caseworkers made it conditional: the girls could attend only if their father wasn't invited. Her sister had invited them without hesitation, never imagining the system could decide who belonged at her own wedding. She chose her dad. Amira missed the wedding.

Sam, at 15, wanted to fly overseas with his 13-year-old brother to visit extended family. His carers supported it. His mum supported it. He'd flown alone before safely. The Department said no without explanation, although most likely because it sat outside the Department’s narrow risk management processes, reflecting a culture more focused on avoiding liability than supporting safe, meaningful experiences for young people.

Reese, at 16 and struggling with suicidal thoughts, reached out to a care worker he'd known for two years. He just wanted somebody to talk to. Instead, the worker called police and an ambulance. Reese was put on a 72-hour suicide watch, then isolated from everyone, his devices removed. It took years before he could talk about his emotions again.

.png)

When parents and carers are judged rather than supported

Being assessed is not the same as being supported. When the system approaches parents and carers with suspicion rather than belief, it creates shame, not motivation to change. The difference between a family staying broken and a family healing often comes down to a single moment: whether someone was willing to see the person, not just the problem.

Emma was young, struggling with addiction and learning to be a mother when her son was removed at three years old. She was completely honest with the Department about where she was at. But they made up their minds about her after just one meeting. A caseworker later told her in court that her son would never come home until he was 18. That there was no chance. For five years, Emma wasn't trying because she believed it was hopeless. Then she got a new caseworker who asked one question before Emma signed away guardianship: "Are you sure?" That caseworker saw Emma's sobriety and her capacity to change. If she hadn't asked, Emma's son may never have come home.

Mark, a foster carer, faced similar judgement when he refused to comply with a new policy. His 14-year-old foster son Luke cut firewood with a chainsaw, lit fires every night and helped with farm work. A new policy was introduced by the foster care agency requiring Mark to install a fireplace guard. This made no sense for their situation. When Mark reasonably explained that he wouldn't install it, he was written up as non-compliant. The system didn't trust his judgement about the young person he lived with and had a relationship with.

By contrast, Megan experienced what belief looks like in practice. When her children were removed, she couldn't walk past the cereal aisle without hearing their voices in her head. Then Sarah, a peer worker, reached out to her: "I'm another mum who's been through this too." Sarah didn't start with paperwork. She asked how Megan was coping. She called when she said she would. She sat beside Megan in meetings and explained the jargon. When Megan cried after family time, Sarah didn't tell her to be strong. She said it was okay to grieve. That belief gave Megan hope.

Young people needing permission to just be kids again

Young people in care often stop being children and become “cases”. They're assessed, managed, monitored. When someone sees them differently, when they're treated like kids who deserve to have fun or be silly or have their own moments, it changes something inside them. These are the moments they remember for life.

Jordan was struggling in residential care after losing two friends he'd known since entering the system. One care worker noticed. Instead of scheduling a counselling session, he took Jordan out for the afternoon, bought him lunch and took him to a rugby game. Jordan watched him tackle and score. He couldn't help but cheer. It was against the rules to introduce young people to your personal life, but this worker was willing to break the rules. He showed Jordan that he wasn't just a number or a case. He was still a kid who deserves to have fun.

Amy and her brothers had a test for case managers: they'd ask them to sing in the car. In one year they had three different workers. The first two wouldn’t sing. But the third one giggled and sang with them without hesitation. She looked at them like they were humans, like they were children. She was always happy to see them. What made those moments special was that it felt like they were in their own harmony. They were just able to be kids, to be them. She was the only case manager that ever felt real to them. They're still in touch today.

Good work requires the courage to push back

The system is built to follow procedures. But the best work happens when someone decides the person in front of them matters more than the procedure. This requires courage. It requires workers to be willing to question directions and trust their own judgment about what's actually needed.

Zara had been working clinically for almost 20 years when she arrived at a home to deliver therapeutic parenting skills. The mum she was seeing had her kids come home after six years in care, was pregnant with a third child, and had no support network. But there was a housing inspection coming. Holes in the walls meant potential homelessness in 72 hours. Zara dropped the plan. She went to Bunnings, bought plaster and paint. She and the mum spent the day patching walls together. In that moment, this mum didn't need therapeutic parenting skills. She needed someone to see that her house was falling down.

Maya arrived at a home where the floors were dirty. The eldest child had just returned after four years in care. The family had a lot going on. Her manager directed her to make a report to the Department, even though it didn't meet the threshold for risk of significant harm. She could have cleaned the floors herself or arranged a cleaner. When the family found out it was her who made the report, they told her she wasn't welcome back. The placement broke down soon after. Maya later reflected that she wished she'd had the courage to challenge that direction. The system hadn't given her permission to use her judgment.

.png)

The significance of relational care

All these stories challenge us to question the system’s rules and procedures when they just don’t make sense. In protecting itself, is the system asking people to suppress their humanity, which is the very thing that makes real care possible?

Relational care means recognising that Emma was capable of change. That Clare's Pop was her family regardless of biology. That Reese needed a conversation, not a crisis intervention. That Sam and his brother could handle a flight the airline itself considered safe.

It means trusting Mark's judgment about fire safety on a farm. It means celebrating when Jordan's care worker broke a rule to give him an afternoon of normal teenage joy. It means creating space for workers like Zara to respond to actual needs rather than predetermined plans and supporting workers like Maya to have the courage to push back when policies don't serve people.

Getting this wrong isn't measured in policy breaches or compliance rates. Yet there are real relational costs at stake. These can be seen in missed funerals and weddings, in five years of lost mother-son relationship, in young people who stopped talking about their emotions after asking for help.

Moving forward

These stories are an insight into what is happening across the out-of-home care system. Moments where bureaucracy wins over humanity, or conversely, where someone chooses a person over a procedure.

The people in the system already know what works. Young people need connection, not just services. Parents need someone to believe in them, not just assess them. Carers need to be trusted, not just monitored. Workers need the space to be human, not just compliant.

If you've got a story to share or you want to connect with us about this work, head over to our contact page. We'd like to hear from you.

Humans of Care Stories

He was my pop, but they didn’t consider him my family

"When I was living in a Kinship Arrangement 6 hours away from my family, my Pop passed away. He was my Pop, maybe not through blood, but he married my Nanny before I was even a thought. He lasted many years after my Nanny passed away and lived in their home without her.

He became unwell with age. I found out he had passed and requested to my caseworker for my sisters and I to attend the funeral. It fell on deaf ears.

I was walking to my English class one day when I saw my older brother online on Facebook. I messaged him asking why he wasn’t at work, he replied with “it’s Pop’s funeral today”. I remember being overcome with sadness, crying, I walked myself in the opposite direction of my classroom and straight to the office, asking to go home.

I asked my caseworker why we weren’t able to attend the funeral, and they stated ‘He wasn’t your biological Pop, and we aren’t able to ensure your safety if you attended’”

- Clare’s story, a young person with lived experience of the child protection system.

They needed support, not another assessment

“I was working with a mum whose kids had come back home after six years in care. They’d been living with a family member. The return wasn’t easy. The children were deeply traumatised. Sometimes when they were upset, they would put holes in the walls.

Mum had a lot going on. Her children were finally home. She was pregnant with her third child. She had no family nearby. No support network. It was just her. My role was to support her with therapeutic parenting skills, but when I showed up for our session, she was completely overwhelmed. There was a housing inspection coming up. She knew they’d kick her out if they saw the damage. Essentially, she was 72 hours away from being homeless.

So I dropped the plan. Went to Bunnings. Got plaster, putty knives, paint. We spent the day patching up holes together.

In this moment she didn’t need therapeutic parenting skills. Not when her basic needs were at risk. She needed someone to see her and help her.

Because how can you expect parents to apply therapeutic parenting skills when essentially their house is burning down?”

- Zara’s story, a clinician with almost 20 years experience.

I just wanted somebody to talk to

“I want to share a time where red tape and borders got in the way of my personal healing journey and relationships that I’ve had.

I was about 16 and living in residential care. I was in a really dark place. I had been in arguments with my family and had lost a friend. I was feeling really depressed and had suicidal ideations.

I went to talk to a care worker of mine who I'd known for two years at the time, and I told him about my thoughts and asked him for help. I just wanted somebody to talk to. And I told him and the first thing he did was call the police, and then the ambulance.

I was put on a 72-hour suicide watch in the hospital. When I came back home, I was isolated from everyone else. I had all my devices taken off me and put into pretty much house arrest, which did some major damage in the long run.

I'm only just now getting back to talking about my emotions and going to see therapists, so it had quite a lasting impact.

Unfortunately, the way that the system is built, a lot of people fail to see that we are just kids, and all we need is help and somebody to admit that they care for us and show us that we matter. The system really does need to change.”

- Reese’s story, a young person with lived experience of the child protection system.

I could have just cleaned the floors

“The floors were dirty when I arrived. My manager directed me to make a Helpline report to the Department, even though it didn’t meet the threshold for “Risk of Significant Harm”. I wish I had pushed back, but I didn’t.

They had two young children in the home, and their eldest child had just turned up unexpectedly after leaving their foster carer’s home. It was the first time in over four years that the parents had seen them. They had a lot going on.

I could have offered to clean the floors myself. Or maybe we could have arranged for a cleaner.

When the family realised a report had been made, they knew it had to be me and told me I wasn’t welcome in their home again. I had broken their trust, and over something so trivial. The placement broke down soon after for their eldest child.

Looking back, I wish I had challenged this direction, but I didn’t have the courage or language. It was a missed opportunity to do something really meaningful.”

- Maya’s story, a caseworker of 3 years.

I missed my own sisters wedding

“When I was in a placement in a small rural town, far over the mountains from where I grew up, an invitation arrived. My oldest sister was getting married by the beach, a huge day for our family and my sisters and I were invited!

The beach was always a place of fun and freedom for us. I could picture her in her dress, waves crashing behind her, everyone laughing and celebrating together. I wanted so badly to be there.

When I told my caseworkers, they didn’t give me an answer. They said they needed to talk to my sister first. The wedding was months away, but the usual ‘wait for word from the caseworkers’ took weeks.

I don’t even really know when they asked her or what was really shared or planned.

Eventually though the news was given to us, our sister was told us girls could attend but only if our father wasn’t invited. It was an awful ultimatum to throw at her, while she was already trying to plan a wedding. She had invited all of us without hesitation. It never crossed her mind that caseworkers could decide who “belonged” at her own wedding.

In the end, she chose to have our dad there. He was her dad too, the man expected to walk her down the aisle. From what I’ve been told, he behaved himself that day. But I wouldn’t know. Because I wasn’t there.

I was 12 or 13 at the time. Old enough to feel the weight of missing it, young enough for it to really sting. Missing that milestone didn’t just mean missing the wedding… it meant missing a chance to grow closer with my sisters and brothers, to share a memory we should still be talking about now.

Looking back, what hurts most isn’t only the day itself. It’s how decisions were made around me, not with me. How something so beautiful could turn into another reminder that I didn’t have a say.

- Amira’s story, a young person with lived experience of the child protection system.

I was still a kid who deserves to have fun

“I was living in residential care. I’d been in that particular residential home for about a year at the time. It was the fifth residential home I’d lived in in six years.

I was really struggling. I’d just lost two friends. They weren’t just my friends they were my brothers. I knew them from the day I entered care. They knew me so well too. From the first day it was like we were on the same wavelength. They were my brothers.

One of my care workers knew I was struggling, but he didn’t even know how bad it was. He took me out of the home for the afternoon. He brought me lunch and took me to watch him play rugby.

I remember the day so clearly. I remember watching him up run out with his team. I remember watching him score and tackle other players. It was like thunder when he tackled someone. I remember a man behind me going berserk watching the game. It was the funniest thing, I’m quite a quiet person, but during his game I couldn’t help myself but cheer.

Up until that day it was the most fun I’ve ever had.

It was against the rules to introduce young people to your personal life in any way but he was willing to break the rules to help me. He showed me that I was not just a number, not just a case, but was still a kid who deserves to have fun.

- Jordan’s story, a young person with lived experience of the child protection system including residential care and 11 months in hotels

I didn't give up because she never gave up on me

"I still remember the day my children were removed, it felt like my whole world shattered in a single moment. Every room in my small unit felt too quiet. The grocery store became unbearable; I couldn't walk past the cereal aisle without hearing my kids' voices in my head. The shame in my community was crushing, and the meetings with caseworkers left me feeling smaller every time. I didn't know what was expected of me or how I was supposed to keep going.

Then one afternoon, my phone rang. It was Sarah who said she was a peer worker. At first, I was wary of her being just another professional but her first words felt different. She said "I'm another mum who's been through this too." That was the first time I had heard someone speak who truly understood.

Sarah didn't start with paperwork or programs. She asked me how I was coping and shared a little of her own story, just enough to let me know I wasn't alone. For the first time in months, I felt a flicker of relief.

Over the weeks, she became someone I could rely on. She called when she said she would. She met me before meetings, sat beside me, and explained the jargon no one else bothered to unpack. When I cried after family time, Sarah didn't tell me to be strong, she told me it was okay to grieve, that those feelings were normal.

Sarah helped with the small, practical things too, like organising documents and role-playing conversations so I could speak up in meetings without freezing. But what mattered most was the way I felt believed in.

I didn't give up because Sarah never gave up on me. Even when I felt like the worst mum in the world, she reminded me of the things I was doing right. She saw me as a person, not a case file.

Our relationship didn't magically restore my children. But it gave me something I hadn't had for a long time, hope. Hope that I can survive this. Hope that change is possible. And hope that I wasn't walking the path alone.”

- Megan, a parent with a child who was in foster care.

It felt like they didn’t trust us to be OK, even when everyone else did

“I was 15 and my brother was 13. We had the chance to visit family overseas. It would have been a 12-hour flight. Just the two of us. Family dropping us off at the airport. Family waiting on the other side to pick us up.

The airline didn’t even consider us as unaccompanied minors as we were both over 12. I’d taken a flight alone before and was fine. I was safe. Our carers were in support of us going. So was our mum.

But DCJ said no. They gave us no real explanation. They just said no.

We missed out on a rare opportunity to spend time with extended family. I felt really frustrated. And honestly, it felt like they didn’t trust us to be OK, even when everyone else did.”

- Sam’s story, a young person with lived experience of being in foster care.

If she hadn't asked 'Are you sure?', my son may never have come home.

“I was 14 when my son Ryan was born. When he went into care three years later, I was living with my nan. The department decided he should stay there too, but then told me I had to move out.

Suddenly I went from having a home to being marked as homeless on all my paperwork. I couldn't believe it. My nan and pop were trying to look after Ryan while also wanting to support me, but they were put in an impossible position. They were told to watch me if I was in the house because DCJ didn’t trust me being around Ryan.

It tore our family apart. They were struggling with the choice between helping their granddaughter or their great-grandson. I felt horrible for putting them in that situation, but I desperately needed support. I was going through the worst time of my life, and suddenly I'd lost my home and my main source of help.

I was really honest with DCJ. I never lied. I said I'm an addict and I've just got a lot going on and I don't know how to be a mum right now. I can't be a mum right now. I was so honest and they just gave me the flick and that was it. They did one meeting with me in the office and they never met with me again.

I remember being at court when I saw that little box ticked to say that restoration was not going to happen. Seeing those words 'final orders' kind of set it off for me. It said he wasn't coming home. But not only that, my caseworker at the time was also saying, 'Your child is never coming home until he's 18 years old. He will stay a child in the out of home care system. There is no chance.'

So for five years, I wasn't trying, because I thought he was never coming home. For five years we lost a relationship that we could have been growing. My son didn't have a mother.

Five years later, I had a new caseworker. She was the most amazing caseworker. She visited me early on and brought paperwork for me to sign which would mean another family would have full guardianship of Ryan. Just before I signed, she asked me, 'Are you sure you want to do this?' I told her it was the only option. She said it wasn't. She asked me if I was sober, which I now was. She said, 'Don't sign it.' She told me I could apply for a Section 90 restoration and they would support me. So that's what I did.

If she hadn't asked 'Are you sure?', my son may never have come home.

- Emma, a parent with a child who was in foster care.

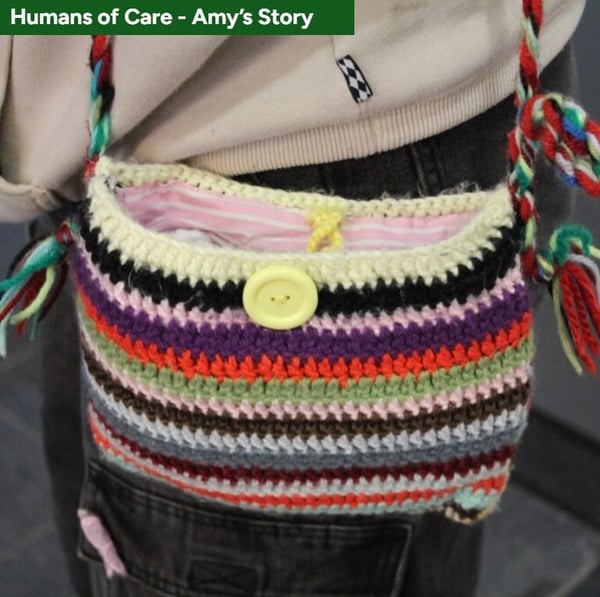

We were just able to be kids, to be us

“Me and my brothers had this game to test case managers, to test if they were cool or not.

We usually had frequent changes in case managers. In one year, we had three different workers. When we finally got our third one, we decided we liked her and wanted to test her. So, while sitting in the back of her car, we asked her to sing.

When we asked her, she immediately started giggling and thought it was the funniest thing. And she sang.

We weren't far from home when this happened, and when we got there, we weren't quite ready for the car ride to end. We were having so much fun.

She looked at us like we were humans, like we were children.

She was always so happy to see us. She said it was a pleasure to work with us.

What made those moments extra special for us was that it felt like we were in our own harmony when we were with her. We were just able to be kids, to be us. She was so cool with us.

She was the only case manager that ever felt real to me.

We're still in touch today.”

- Amy’s story, a young person with lived experience of the child protection system.

She had a real opportunity to go home, but her relationship with family and culture wasn’t a priority.

"I had been working with a young girl for a few months. She had recently had a placement end and was living in an ACA (alternative care arrangement) which is essentially an Airbnb with staff.

I was encouraged by my managers and the Department to conduct intensive family finding. Seeing a child go home to family is the dream of many caseworkers.

I tracked down her father, who lives overseas with his wife, children, and a home with space for his daughter. He had a closeknit family and strong connection to culture and community.

He wanted his daughter home more than anything but was hesitant to engage. He'd spoken to many caseworkers before about restoration. They made promises to support him but moved on before any work could be done.

It took months to earn his trust. We spoke frequently and built a great relationship. He shared his worries and past experiences, and I told him how important it was for his daughter to be with family and in culture and that I believed in him. There were no safety concerns, just a tricky legal process to get through with him being overseas.

I had the honour of being with his daughter when they spoke via video call. They had a beautiful connection. He listened to her, shared stories, and taught her what her name meant and who her family was.

At the same time, the agency pursued other options. We all wanted her out of the ACA quickly. A lovely carer was found who met many of her needs.

This didn’t change my desire for her to return to family. But I noticed an immediate change in tone from management and DCJ. The conversation shifted from praising dad and restoration to saying he hadn’t engaged to their standard, and that she was now with a wonderful carer.

I went from having support, time and resources to being told this was no longer a priority. She had a real opportunity to go home, but her relationship with family and culture was no longer deemed important once she left the ACA.

I spoke to her dad and encouraged him to keep trying for restoration, but I could see how disapointed he was. I had failed him on my promise to help. I was so disappointed. I believed those around me wanted long-term family connection, but they were more focused on the quickest solution.

This was one of the heartbreaks of my career and ultimately contributed to my decision to leave casework."

- Susan’s story, a former caseworker.

Carers need to be trusted to use their judgement.

“When Luke was about 14, my agency brought in a new policy. Every fireplace needed a fire guard around it so kids wouldn't get burnt. But here's the thing: we live on a property. Luke goes out and cuts the firewood with a chainsaw and an axe. He lights the fire every night. We're burning off paddocks, doing farm work. He's doing all of this safely, learning skills and being trusted.

I said to them, this doesn't make sense for our situation. It wasn’t age appropriate. If I had a two year old crawling around who might touch the fire, absolutely, I get it. But this is a 14 year old who lights the fire every night. A fire guard isn't going to protect him.

They told me I had to. Policy is policy.

I said I wouldn't be doing it. And that was basically written up as me refusing to comply. Like I was some kind of dangerous carer.

It was policy over common sense.

You know, I don't like institutionalised practices. Which so many of organisations are. It's all about ticking and flicking, you know. A caseworker comes out once a month, tells us what we need to do, does a bedroom check, then we don't see or hear from anyone again for another month till it's time to do that tick again.

I think carers need to be trusted to use their judgement. We're the ones living with these kids day in and day out. We know what they need.”

- Mark, an experienced foster carer.

When Mark was asked why he chose this photo, this is what he shared.

“This fireplace reminds me of the out-of-home care system and the children within it. Raw, earthy, and rustic - built from strong, natural foundations. But also pieced together in straight, confined blocks, shaped and contained by what’s around them. Each stone tells its own story - rough edges, different shades, imperfect but holding firm together. Just like foster children - resilient, chiseled, a rough and tough facade but so much warmth behind it, beautiful in their rawness, yet living within a system that tries to square off their edges to make them fit. Still, even within those walls, there’s so much warmth, purpose, and heart - because what’s built with love, care and authenticity only has positive outcomes for all of those who are part of it… those who nurture, those who support, and most of all, those who finally find a place to belong.”